Online seminar November 26

16.00-18.30 CET

Since 2019, Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art has initiated a series of seminars and artistic commissions on the topic of the visual representation in public space of Sweden’s colonial past and its contemporary consequences.

For the project Possible Monuments? artists and writers have been invited to respond to Franska tomten, a site in Gothenburg harbour with connections to Sweden’s colonial activities in the Caribbean.

Their responses are hosted here and have been discussed in an online seminar on November 26th.

The project is organised in collaboration by Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporary Art and Public Art Agency Sweden.

Contributors: Aria Dean, Ayesha Hameed, Daniela Ortiz, Fatima Moallim, Hanan Benammar, Jimmy Robert, Morgan Quaintance, Runo Lagomarsino, Ylva Habel, in dialogue with Lisa Rosendahl, curator GIBCA 2019 & 2021.

Considering recent actions directed at public statues with colonial connotations, as well as the underdiscussed Swedish involvement in colonial trade, the seminar addresses the need of remembrance and memorialization in honour of the victims of colonialism and its contemporary consequences.

How can we open existing monuments to re-contextualization? What role can art play in making Swedish colonial history publicly visible? How can new monuments, be it material or immaterial, trace past to present? How should a potential future commissioning process be conducted to avoid reproducing existing structures of inequality and exclusion? Is there indeed such a thing as a possible monument, and if so: for whom and by whom should such monuments be made?

Franska tomten got its name in 1784 when it was exchanged for the Caribbean Island of Saint Barthélemy as part of a trade agreement between Sweden and France. While the French were given free trade rights in Gothenburg, Sweden took over the colonial administration of Saint Barthélemy. Until 1847, Sweden’s economic activities connected to the island were almost exclusively concerned with slave trade. In 1878 the territory was sold back to France.

Today, no official information acknowledging Sweden´s involvement in colonial violence, nor any commemorative gesture honouring its victims, exist on site. Furthermore, there are no public monuments or memorials in the country as a whole acknowledging Sweden’s colonial relations and those who suffered their consequences. The country´s colonial activities, of which Saint Barthélemy is but one example, are also not generally part of how the narrative of the formation of the Swedish industrial Welfare State is told.

What does remain on site at Franska tomten are artworks commissioned in the first half of the 20th century by modern day transatlantic shipping companies. As power structures of colonialism, anti-blackness and white supremacy continue to inform our present, artists are invited to reflect and comment on these visual traces of political and aesthetic ideologies.

The project is also part of the biennial’s ongoing engagement with Franska tomten and alternative historiography. Previous seminars and commissions related to Franska tomten include: Franska tomten: Shedding Light on Swedish Colonial History, in collaboration with Public Art Agency Sweden, with the participation of artists Jeannette Ehlers and Eric Magassa, GIBCA curator Lisa Rosendahl, Judith Wielander, curator of Visible Projects, Mathias Danbolt, art historian; Sarah Hansson, curator for Göteborg konst and Lotta Mossum, curator for Public Art Agency Sweden; Swedish Colonial History – Abolition of Slavery and Contemporary European Discourses, lectures by Françoise Vergès and Klas Rönnbäck; Listening to Colonial Traces in Public Space in Gothenburg, lectures and panel with Maria Ripenberg, Lena Sawyer, Nana Osei-Kofi, Sandra Grehn and Therese Svensson; and commissions in public space by Eric Magassa and Ibrahim Mahama.

The eleventh edition of the biennial, The Ghost Ship and the Sea Change, opens in two phases on June 5th and September 11th, 2021.

Trading Winds is a multichannel sound installation and series of textile panels installed in Gothenburg. It references the twin city plans based on canal systems made for Gothenburg and Batavia (now Jakarta) and the 1852 hurricane that struck Saint Barthélemy, Sweden’s only slave colony in the Caribbean. Trading Winds thinks about tunnels of wind through these two cities and the Caribbean island and their relationship to colonialism and slavery.

Trading Winds is plotted along a five-minute walk that starts from Packhusplatsen 6–7, the canal side of the Customs House, where goods from the Transatlantic slave trade were stored. It ends at the Gothenburg City Museum, located in the former East India Trade Company building. Over the course of this five-minute walk then, we travel from one phase of Franska tomten’s history to another—from its participation in the Transatlantic slave trade, to its role as a hub of colonial trade.

The walk that Trading Winds traces along the historical canal of Franska tomten evokes another set of canals: those in Batavia, the old Dutch bastion town in contemporary Jakarta that was twinned with Gothenburg as they were both designed under the Dutch colonial empire. It links this buried history with another lesser-known history: that of Sweden’s only colony in the Caribbean, Saint Barthélemy.

This is what Trading Winds will look like. Installed along the canal as one walks from the Customs House to the City Museum, will be a series of speakers that play street sounds recorded in Saint Barthélemy and Jakarta. In St Barthélemy the sound will be recorded during a walk through the historic port of St. Gustavia. And in Jakarta, the sound recorded will be from a walk along one of the canals in the historic Batavia.

As you walk from Packhusplatsen 6–7 you hear the sound of St. Gustavia, and when you arrive at the City Museum you hear the sounds of Jakarta along the canal. During the walk the sound of Saint Barthélemy will gradually overlap with the sound from Jakarta forming a blurred soundscape. As you near the City Museum, the sounds of Jakarta will get louder and those of Saint Barthélemy will fade, but in between there will be an indeterminate sonic blending between the two cities that Gothenburg is historically and intimately connected with.

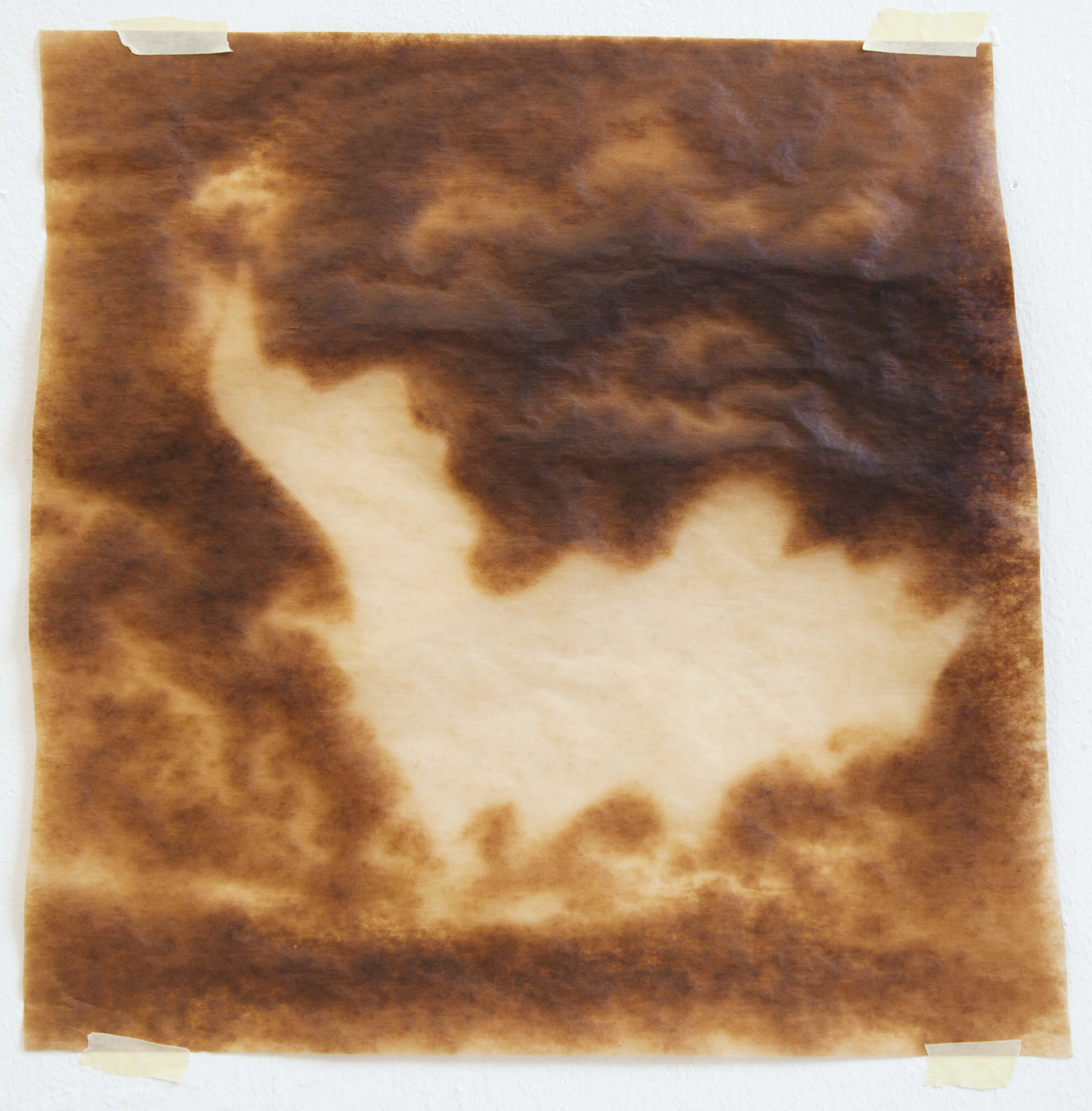

The textile panels that will be planted above each speaker along the canal refer to both Saint Barthélemy’s and Batavia/Jakarta’s colonial trading history. Goods being traded in Batavia included nutmeg, peppers, cloves, cinnamon, coffee, tea, cacao, tobacco, rubber, and sugar. The canals were not suitable for the conditions in the region: they constantly silted over and had to be dredged: an ecological manifestation of the colonial violence of imposing modular city planning. Saint Barthélemy, a volcanic and arid island, could not support the conditions for a plantation system of slavery, so the Swedes established the island as a free trade zone for the purchase of slaves. This was an even more dire commodification of enslaved men and women. The textiles will bear traces of that history—from Jacques Gentes’ unsuccessful attempt to cultivate cacao in the 17th century; to the commercial production of salt, visualized here in the mangroves that were able to grow the saline swamps around the island and that mitigated the currents of the windy sea that buffeted the island; to the flamboyant, a tree indigenous to Madagascar but planted in tropical and subtropical regions all over the world and evoked here to consider flora disseminated through colonialism; and finally to the barbary fig, which is reported to have been used as a cactus fence as a defense against rival colonizing countries from Europe, like Britain.

The textiles will be dyed using pigments from these spices and plants. And the images themselves will form the basis of what is printed onto the fabrics. Their colour and scent will fade with time in the outdoor weather of Gothenburg. Winds fuelled the currents of trade winds in the Indian Ocean, steering ships to all parts of the world, and blew seeds from island to island in the Caribbean.

Images from Wikipedia

Sample sounds from Freesound:

“embedded muezzin-chants in moderate traffic-noise at 12h am” (jakarta) source https://freesound.org/s/27520/

author palem

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons 0 License.“A windy afternoon in St Croix. Birds singing, wind blowing through house.” source: https://freesound.org/people/nyseagull/sounds/400379/

author: nyseagull

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons 0 License. https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Ayesha Hameed lives in London, UK. Since 2014 Hameed’s multi-chapter project ‘Black Atlantis’ has looked at the Black Atlantic and its afterlives in contemporary illegalized migration at sea, in oceanic environments, through Afrofuturistic dancefloors and soundsystems and in outer space. Through videos, audio essays and performance lectures, she examines how to think through sound, image, water, violence and history as elements of an active archive; and time travel as an historical method.

Recent exhibitions include Liverpool Biennale (2021), Göteborg International Biennial for Contemporry Art (2019), Lubumbashi Biennale (2019) and Dakar Biennale (2018). She is co-editor of Futures and Fictions (Repeater 2017) and co-author of Visual Cultures as Time Travel (Sternberg/MIT forthcoming 2021). She is currently Co-Programme Leader of the PhD in Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths University of London.

Eurocentric narratives concerning colonialism and racism currently describe global south, migrant and racialized communities as defeated groups in order to be able to paternalise them and continue exercising control and power over them.

The explicit erasure of the historical struggles and victories of anticolonial movements is a crucial component in the attempt of reinforcing and maintaining the contemporary racist system. This erasure also fortifies the position of white European societies of not recognizing the existence of an antiracist movement in the actual European context.

Claiming and maintaining alive the memories of anticolonial resistances is crucial for the struggle against European institutional racism, is crucial for understanding the long-term battle against white supremacy and it’s violence while bringing to our days strategies carried out in the past. In the Celebration of Our Struggles Is Their Collapse proposes to install two garlands that will be tied at Franska tomten and around the Delaware monument.

Each garland will resemble the rope usually tied around monuments in order to tear them down and will have printed images of different moments of anticolonial struggles related to European and Swedish colonialism.The garlands will narrate diverse episodes of anticolonial resistances and include phrases which encourage the tear down of colonial monuments and representations such as the ones at Franska tomtem and the Delaware monument.

Daniela Ortiz (born 1985, Peru) lives and works in Urubamba. Through her work Daniela Ortiz aims to generate visual narratives in which the concepts of nationality, racialization, social class and genre are explored in order to critically understand structures of colonial, patriarchal and capitalist power. Her recent projects and research deal with the by European institutions in order to inflict violence towards racialized and migrant communities. She has also developed projects about the Peruvian upper class and its exploitative relationship with domestic workers. Recently her artistic practice has turned back into visual and manual work, developing art pieces in ceramic, collage and in formats such as children books in order to take distance from Eurocentric conceptual art aesthetics. Together with her artistic practice she is mother of a three-year old, gives talks, workshops, do investigation and participate in discussions on Europe’s migratory control system and its ties to coloniality in different contexts.

Franska tomten got its name in 1784 when it was exchanged for the Caribbean Island of

Saint-Barthélemy as part of a trade agreement between Sweden and France.

Saint-Barthélemy was a Swedish colony between 1784 to 1878.

I chose to start with these simple facts.

Because I lived in Gothenburg for three years and never once read about Franska tomten. Because I studied in Sweden and never once heard or read that Sweden participated in the Berlin Conference. Because I grew up in Sweden and never once heard about Franska tomten in school.

Colonialism has never existed in Sweden, either in the southern hemisphere or the northern. That’s the official story here, and it amounts to a case of public amnesia, an erasure of the country’s past and present. We have neglected Sweden’s active role in colonial history.

While developing my proposal—or developing an idea for what could become a proposal, or developing a thought as an initial notion that might later become a proposal—these thoughts have haunted me. How do we visualize what has been erased, and forgotten, or what is fragmented or perhaps even ghosted? “The past coexists with the present in this amnesiac country in this forgetful century”, writes Michelle Cliff.

I think it is important to imagine another form for minnes konst (memorial art). I use the Swedish word minne instead of memorial because I think memorial accentuates the past, while minnes konst sets in motion an activity—it moves forward, forcing us to delink hegemonic ways of narrating. There is an urgent need to conceptualize struggles of memory and to critically link mechanisms of memory and forgetfulness in relation to public spaces. Why are some people memorialized and others not, and how can this discrepancy be materialized? These questions have been given even greater emphasis in recent decades with the discussion, conflict, and removal of monuments in public spaces in places like South Africa, Latin America, and United Sates (to mention a few), and with the controversy over the lack of spaces for mourning and memory, as in the case of the victims of right-wing terrorist Peter Mangs in Malmö.

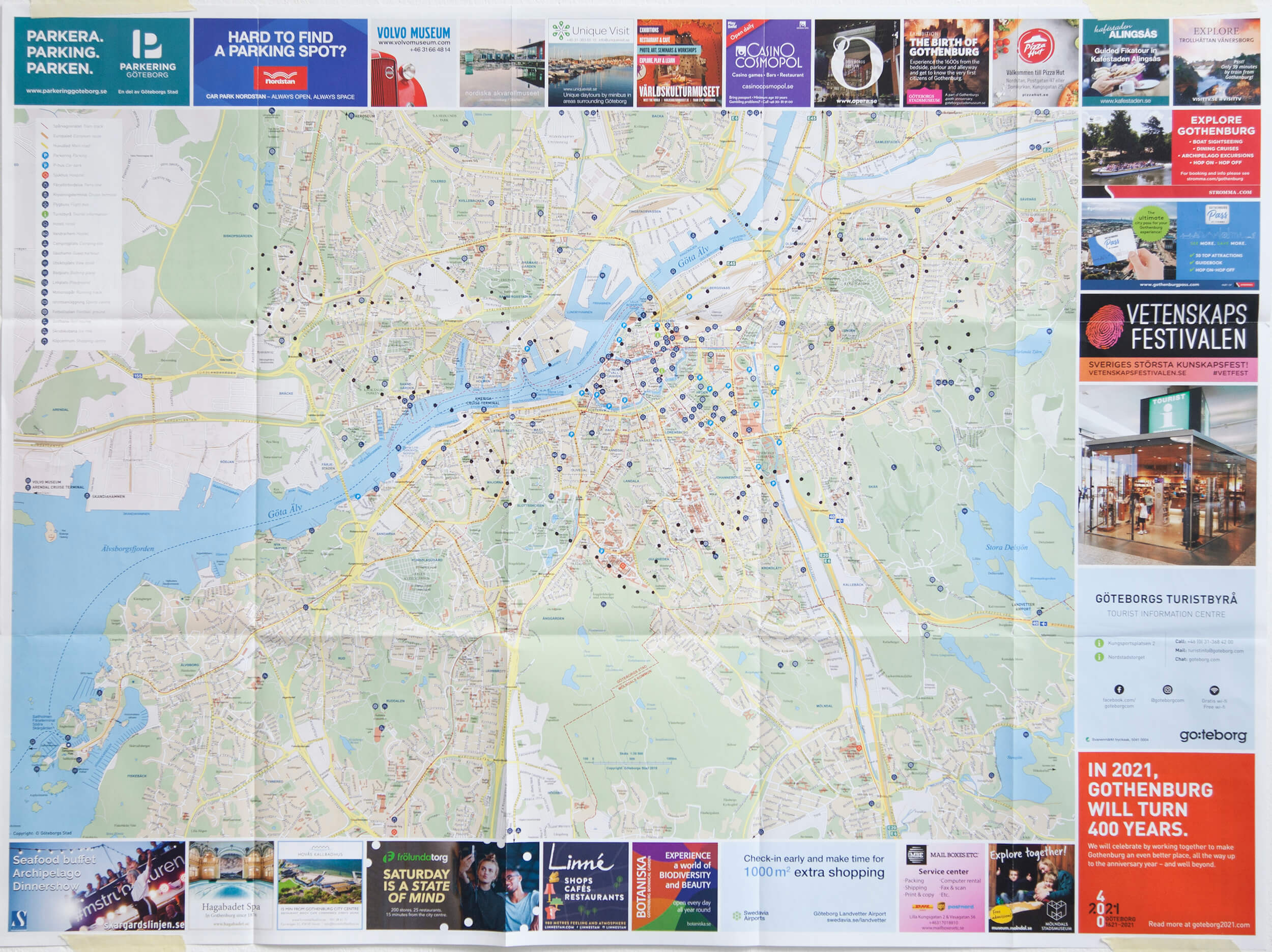

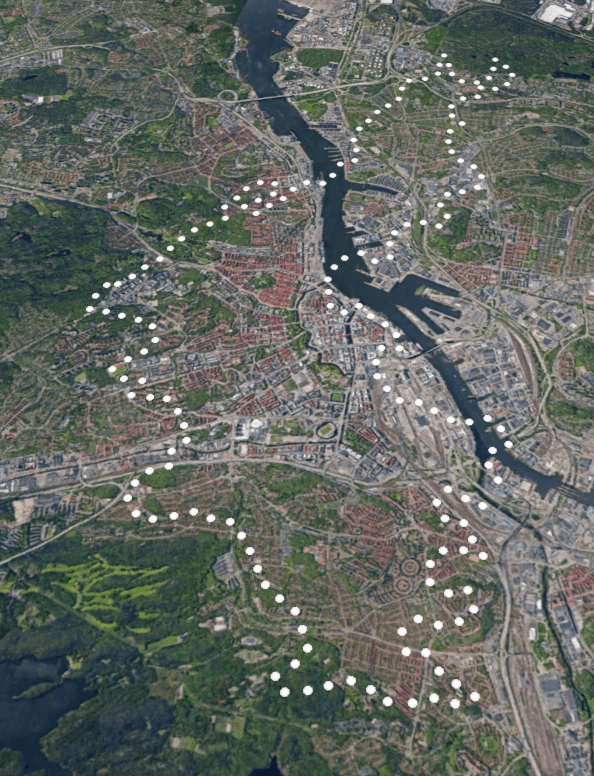

I started to ask myself, why only here? Why only at the Franska Tomten site—as if the colonial paradigm had been limited to that one place? As if there had ever been a definitive endpoint to colonialism. Why can’t I move beyond a single site and imagine a proposal that expands throughout the city, using its materiality and physicality to give form and content to colonial history, while also confronting the presence of colonialism in today’s world. The artistic project also has to include a form for discomfort, a rupture that denies the viewer a safe distance from which to calmly contemplate the horror of the past.

Another question linked to the previous one I asked myself was, why are we once again focusing on the center? I see the proposal as two-fold, in part moving the work out from the center, as a way of manifesting the invisibility and visceral forms of colonialism (it is everywhere) while avoiding yet another focus on the center, and in part avoiding the duality between a center and a periphery. Why should the mourning be in the center? Aren’t the island’s history, people, and struggle connected to the heterogeneous life of citizens—citizens who carry similar histories of displacement, exile, and violence.

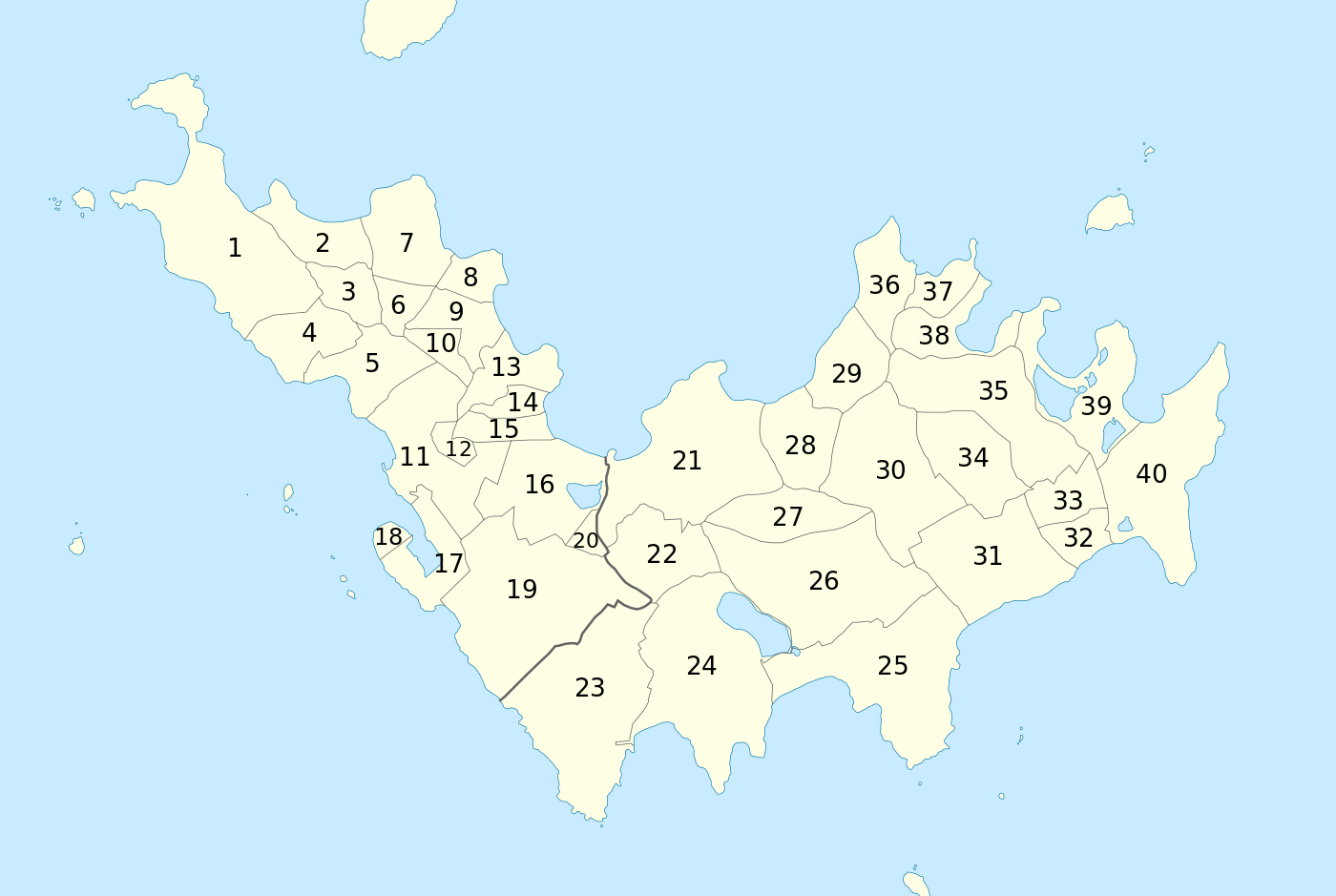

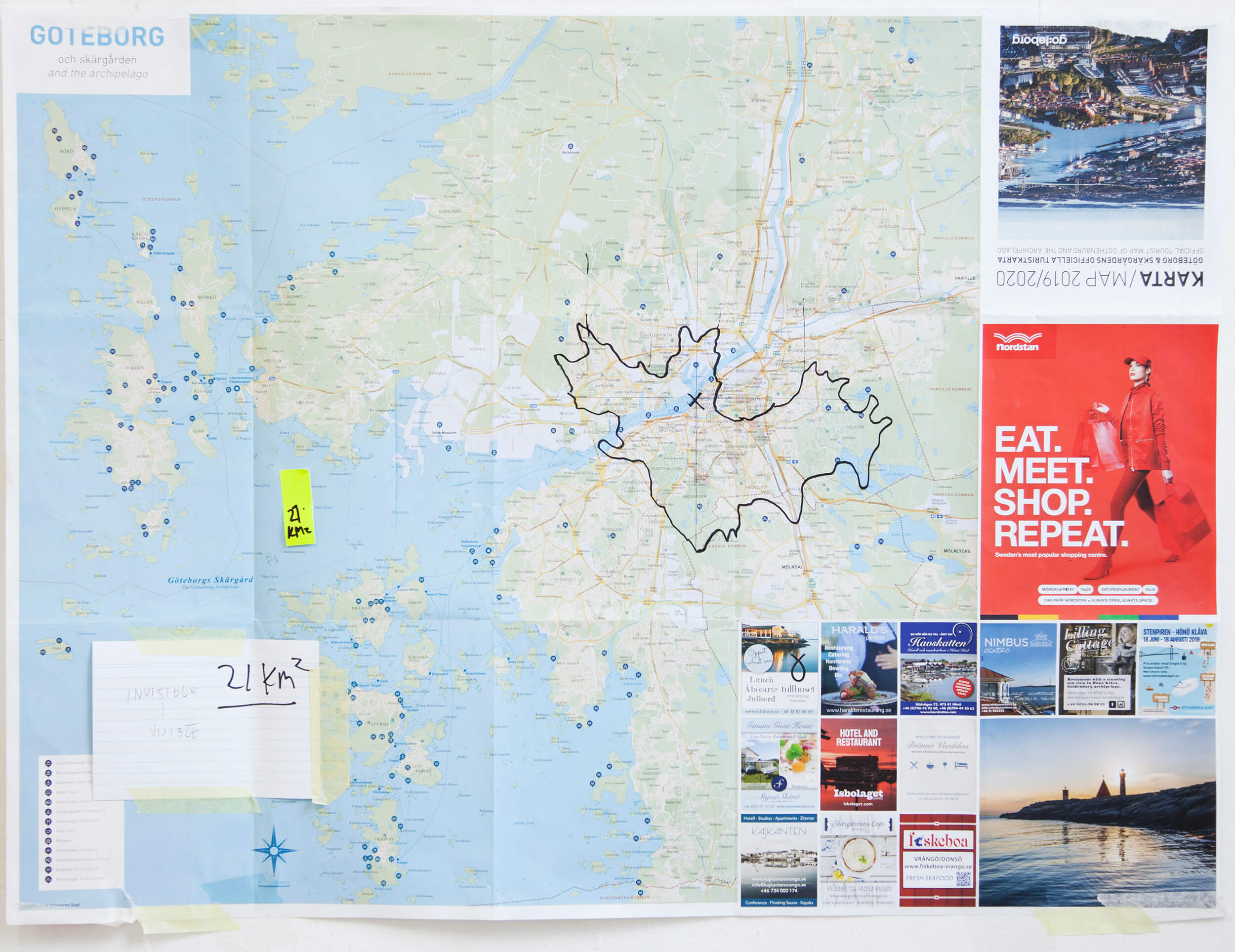

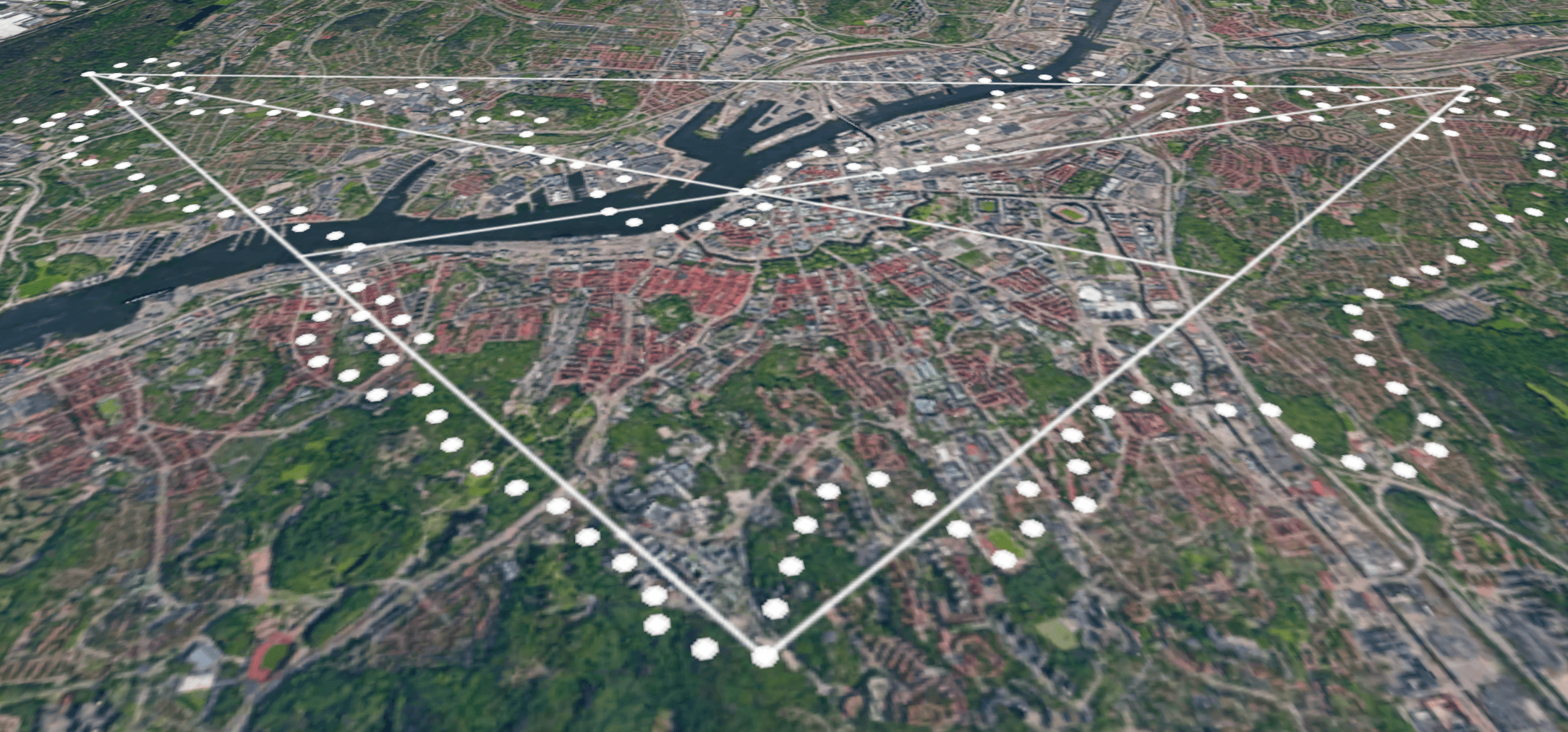

The work itself is very simple. I calculated the perimeter of the island of Saint Barthélemy, measuring

39 km and then I laid it on Gothenburg, I used Franska tomten as the triangulation

framework. By doing so I could imprint physically the island in the correct scale, not in the

city of Gothenburg but ON the city, and by this movement having the land from the south

(the ghost) coming back to the north. To be here.

As the first part of my proposal, from now on, the Gothenburg turist map should include this imprint of the island Saint Barthélemy. This updated map should be the official version of the city.

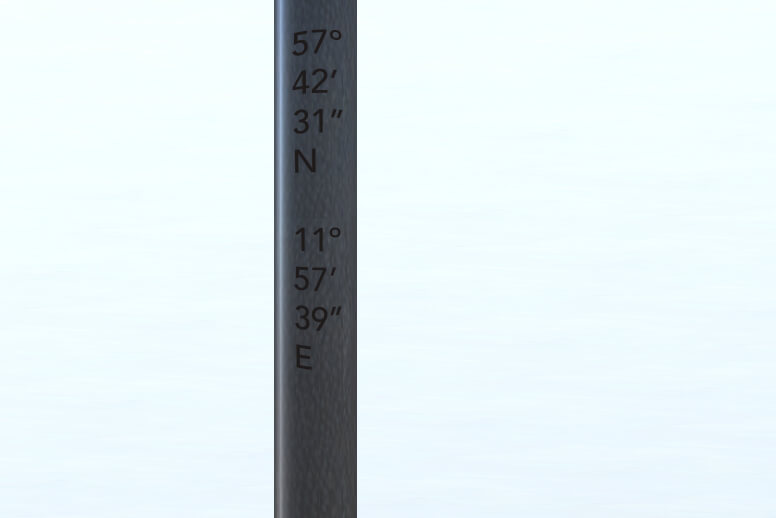

I draw the contour of the island. Every dot becomes an iron bar stuck into the ground measuring 3,5 meter in height. They are placed in a distance of 200 meter creating the map of the island. On each of the iron bars the longitude and latitude of that specific point

on the island is engraved. Making a precise translations of Saint Barthélemy in Gothenburg.

The work can, by its physicality give people the possibility to actually walk around the island, to be on the island, to understand and feel the connection between now, here and there and then. The work is both visible and invisible, only by moving in the city, the whole island appears. This counteracts the erasure, the active amnesia, for, as Anne McClintock writes, “when a nation refuses to remember, neither acknowledging nor accounting for the past, it enters the geography of haunted places and violence is destined to recur with relentless repetition.”

I chose iron for its clear connection to Swedish colonial history: it played an important role in the material system of the slave trade, used for both the shackles that bound them and the “voyage iron” bars forged specifically for use as currency to be traded for slaves. I want them to be stuck into the ground as a metaphor for the violence colonialism visits upon people and land, but also as a visual symbol of protest and a sign of presence.

Bertolt Brecht wrote the play How Much Is Your Iron? in 1939 while in exile in Sweden. The use of iron connects these two moments in Swedish history. It accentuates the way Sweden has always used its industry to gain capital welfare while simultaneously neglecting the political consequences of doing so. Many assert that there was no colonialism in Sweden, there were no Nazis in Sweden, and there is no racism in Sweden. These are statements that should haunt us, and I see Franska tomten and the discussion we can create around it as a collective effort to change that paradigm. As James Baldwin elegantly wrote, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Photo credit: Lotten Pålsson

Digital sketches: Adrian Espinos

Runo Lagomarsino is an artist that lives and works in Malmö, Sweden. Language, geography, and historiography are themes that Lagomarsino revisits in his artistic practice, using materials that often evoke memories or a relationship to something, only to ask us to reflect on the conditions enabling these connections. Lagomarsino’s work points towards the gaps and cracks in our explanation models highlighting language’s precarious foundation. With precise and poetic displacements, he constructs frictions, fractures of blind spots from where to tell other stories.

Recent solo exhibitions include: The Faculty of Seeing, Moderna Museet, Stockholm (2019), We are each other’s air, Francesca Minini, Milano, (2019), EntreMundos, Dallas Museum of Art Dallas, (2018) La Neblina, Galeria Avenida da India, Lisbon (2018)

Selected group exhibitions: Deep Sounding—History as Multiple Narratives, daadgalerie, Berlin (2019), BRAZIL: Knife in the Flesh, PAC, Milan (2018), A Universal History of Infamy, LACMA, Los Angeles, (2017), La Terra Inquieta, Fondazione Trussardi, Milano (2017), Really Useful Knowledge, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid (2014) and Under the Same Sun, Guggenheim Museum, New York (2014) He has also participated in Prospect 4, New Orleans, (2017), The 56th Venice Biennale (2015), The 30th São Paulo Biennial (2012), Liverpool Biennal (2012), 12th Istanbul Biennial (2011),

In 2019, Runo Lagomarsino was Daad artist-in-residence in Berlin.

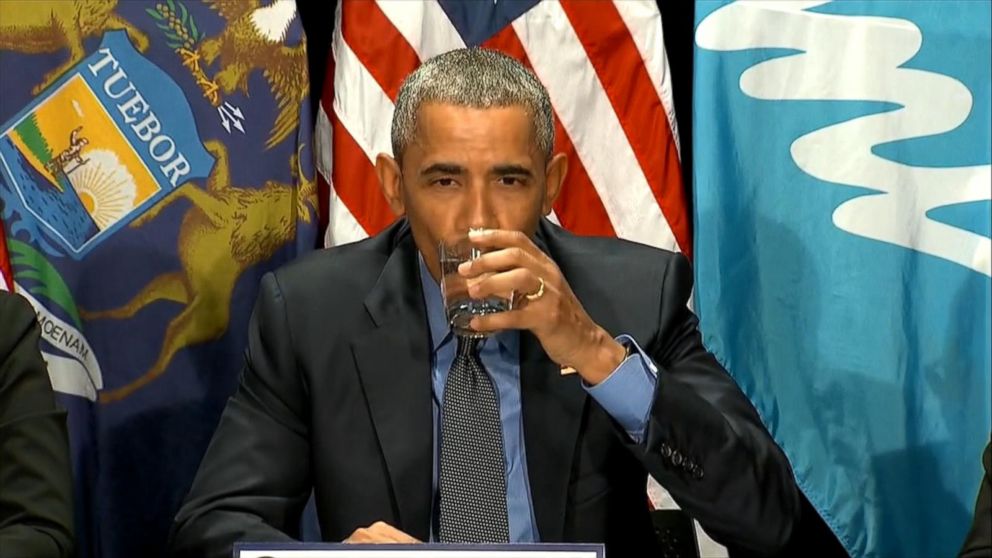

Perhaps the single greatest historical event to solidify Barack Obama’s public reputation as a just, progressive and morally courageous politician was the election, in 2016, of Donald Trump. Less a man than a hulking, orange caricature of narcissistic bigotry, Trump’s ‘pussy grabbing’, fascist courting persona had the immediate effect of making Obama seem the eternal, irreproachable statesman. Almost overnight all mention of his ‘kill rather than capture’ drone bombing policy and the hundreds of civilian deaths caused by it were erased from public memory; as were the weak regulatory reforms that followed 2008’s global financial crisis, and his departmental employment of bankers and economists who led institutions responsible for stacking the sub-prime house of cards. The election of Obama provided the facelift American politics needed; he was a figure who looked like change, but crucially repackaged and redeployed the status quo. Obama was neoliberalism with charm, a winning smile and the rhetorical flourish of historical precedent on his side.

The critical vacuum surrounding Obama’s presidential record provides us with a good example of the cosmetic regime’s core operative dynamic: the veneration of good optics and the simultaneous disregard of questionable conduct. It is a system of judgement that accords almost absolute value to the way things seem over how they are; the appearance over action. In party politics it is the logic of personality over policy; in visual culture aesthetics over attitudes. In each case the approach strengthens the veracity of a given pretense by ignoring uncomfortable, narrative discrepant aspects of a given reality. More than a curious symptom of neoliberal disciplinary societies, the skewed picture of reality presented by the cosmetic regime does harm and is a major concern for a number of reasons. Chief among them is this. The greatest threat to socio-political and cultural progression is the illusion that it is already taking place.

The genealogy of the cosmetic regime’s and its reverence for appearances is likely long and complex. One historical perspective could track its modern roots to Edward Bernays, Sigmund Freud’s nephew and the prototypical PR man who used psychological methods of sale for effective image-based propagandising. Later in the twentieth century it could be argued that at least since the 1960s we have become, as Guy Debord and the Situationists identified it, a society addicted to and enthralled by the spectacle. This century the internet and world wide web have played their part. The image driven nature of social media and much communication online (essentially images and text about images), have helped to deflate reality and inflate the importance of the two-dimensional image, reducing the complexities and terms of discourses, debates, events and states of affairs to those that are captured within its flattened plane. How often are the intricacies of political activism simply reduced to one Instagram friendly image that, in the favoured tagline of Americanised click-bait, will ‘end’ either climate change, racism, homophobia, sexism, inequality, or political corruption? And yet somehow they all endure.

This short text will briefly examine the cosmetic regime’s distortion (that is, the privileging of aesthetics over action) of a single movement, decolonisation. To clarify, this process and the particular type of perceptual distortion it has entailed are most notable in Western societies; in so-called late-capitalist or developed nations where the days of actual colonisation are largely perceived to be over. It is no surprise that the majority of these nations (France, Britain, Sweden, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands etc.) are themselves former colonisers previously engaged in the violent takeover and expropriation of another country’s sovereignty and resources (be they human, mechanical or natural). Today, inside the bounds of consensus ‘post-colonial’ realities, the two opposing ends of contentious debate are focused on the continuance or denial (the so-called ‘left and ‘right’ perspectives) of colonial attitudes and the behavioural and material leftovers of prejudicial value systems. Within the cosmetic regime, the existence or not of this legacy has manifested, to a great extent, as a battle over optics and supposedly through optics to attitudes. As such, a central conflict is being fought over things we can see, material things, monuments and statues that commemorate or celebrate events or figures from the colonial past. The logic goes that the existence of these monuments and statues in the present stand as physical evidence of ingrained discriminatory tendencies within Western societies and the fundamental celebration of colonial exploits in the past. At the same time, Western cultural commentators also frequently project what they feel are the conditions required for reparative satisfaction onto former colonies, namely the removal and repatriation of looted artifacts from national museums.

In effect, demonumentalisation and artifact repatriation are the two complementary concerns that have come to dominate what passes for decolonial debate in the mainstream press and cultural sector in both the UK and US. I suspect it is much the same in Europe. What it again illustrates is how an emphasis on optics within the cosmetic regime, almost always places an emphasis on cosmetic solutions. This is how colonisation and decolonisation, within Western cultural-sector discourse, have largely become understood as metaphorical and symbolic processes (i.e. decolonise art, decolonise fashion, decolonise education, decolonise Hollywood, etc.) but rarely as economic and actual realities (i.e. nobody is calling for the removal of Indonesia from West Papua). Despite the fact that colonial legacies of Western expropriation continue in the form of natural resource drains (mining contracts, rainforest diminishment), structural adjustment programmes, investor state dispute settlements, enforced currencies, capital flight, tax avoidance, money laundering and so on, interested parties in the West continue to argue about objects and the spectacles such objects produce.

In order to illustrate how this process unfolds in public, and how a narrow emphasis on appearances ultimately allows detrimental conditions to continue under the guise of superficial reforms and sacrificial gestures (the removal of statues, the renaming of institutions and so on), both geographical aspects of the cosmetic regime’s spectacular system of redress – that is to say the domestic (the removal of statues, specifically in the UK) and the international (the repatriation of objects to former colonies) – will be examined.

[image The statue of Cecil Rhodes is removed]

It could well be argued, by anyone who has taken an interest in decolonial efforts and agitation over the past five years, that monument and statue removal is not a purely Western affair. The 2015 Rhodes Must Fall (RMF) movement, a campaign to remove the statue of racist former prime minister of South Africa Cecil Rhodes, led by students at the University of Cape Town, was arguably one of the contributing factors that kick-started the appetite for de-monumentalisation abroad. What is indicative of the cosmetic regime’s Western dominance is how the RMF movement was partially framed in the process of influencing domestic efforts. Although the initial flashpoint for the RMF movement was the removal of Rhodes’s statue, the initiative quickly moved deeper into agitating for systemic and structural change in the higher education system in South Africa. Rhodes must fall was followed by ‘Fees Must Fall’ (FMF) a call to significantly lower university fees, which was, I would argue, the more fundamental, socially and economically impactful attempted action of the two. It is easy to see why. The removal of Rhodes’s statue might represent a symbolic victory in the short term, but could it also benefit the other side, so to speak? Could the statue’s removal also allow those maintaining discriminatory and biased systems to defend themselves by using the sacrificial gesture of removal as evidence of significant reform? Could the relief from activist pressure that satisfaction of the symbolic request brings, buy time for the establishment and give them the space to retrench, reorganise and continue with discriminatory practices? I believe the answer is yes, and this is the precise reason why no news of the FMF movement reached British shores.

Of course, while it is difficult to convincingly argue, and most likely improbable, that one individual person or organisation decided to keep news of FMF out of the decolonial conversation, the existence of such a person, organisation or explicitly voiced edict is unnecessary. This is because the nature of what is an isn’t deemed worthy of attention within the cosmetic regime (i.e. aesthetics over action) ensures that the spectacular event is always given more space. Just as certain ways of dressing or behaving are not seen as correct or desirable within certain workspaces, so too is a non-visual emphasis on decolonial agitation or activism seen as unworthy of attention amongst cultural commentators, institutions and the mainstream press. The related British response to RMF, then, was limited to a debate about whether or not the Rhodes Scholarship (an international postgraduate award for foreign students to study at Oxford University, set up in Cecil Rhodes’s honour) should be renamed. No corresponding push to agitate for the reduction or abolition of British student fees took place.

[image Protestors in Bristol removing Edward Colston’s statue]

The recent surge in Black Lives Matter protests in the UK after the killing of George Floyd in the US has also followed this trend. Media coverage and campaigns have centered on the removal of statues deemed celebratory remnants of historic colonial ideals, events and individuals. Activists and interested parties on both sides of the simplified political divide (i.e. the ‘left’ and ‘right’ wings) argued over whether monuments of Winston Churchill and others should be removed, a statue of British slave trader Edward Colston was toppled by protestors in Bristol, and much was made of the Museum of London’s decision to remove the statue of slave trader Robert Mulligan from the plinth in front of its Docklands premises. In addition to the push to demonumentalise came a renewed call to diversify a monocultural mainstream media, professional sphere, system of higher education, and so on. All of these demands had one thing in common, an emphasis on altering the appearance of either monuments or institutions in the UK, but not the state and organisational structures behind them. In other words, the system remained in place, all that was called for was an overhaul of personnel, different figures on podiums and different faces in the work place. Both laudable goals, but not ends in themselves. The point being this: the safest demand for established systems of organisation – be they economic, social, cultural or political – is a demand for access.

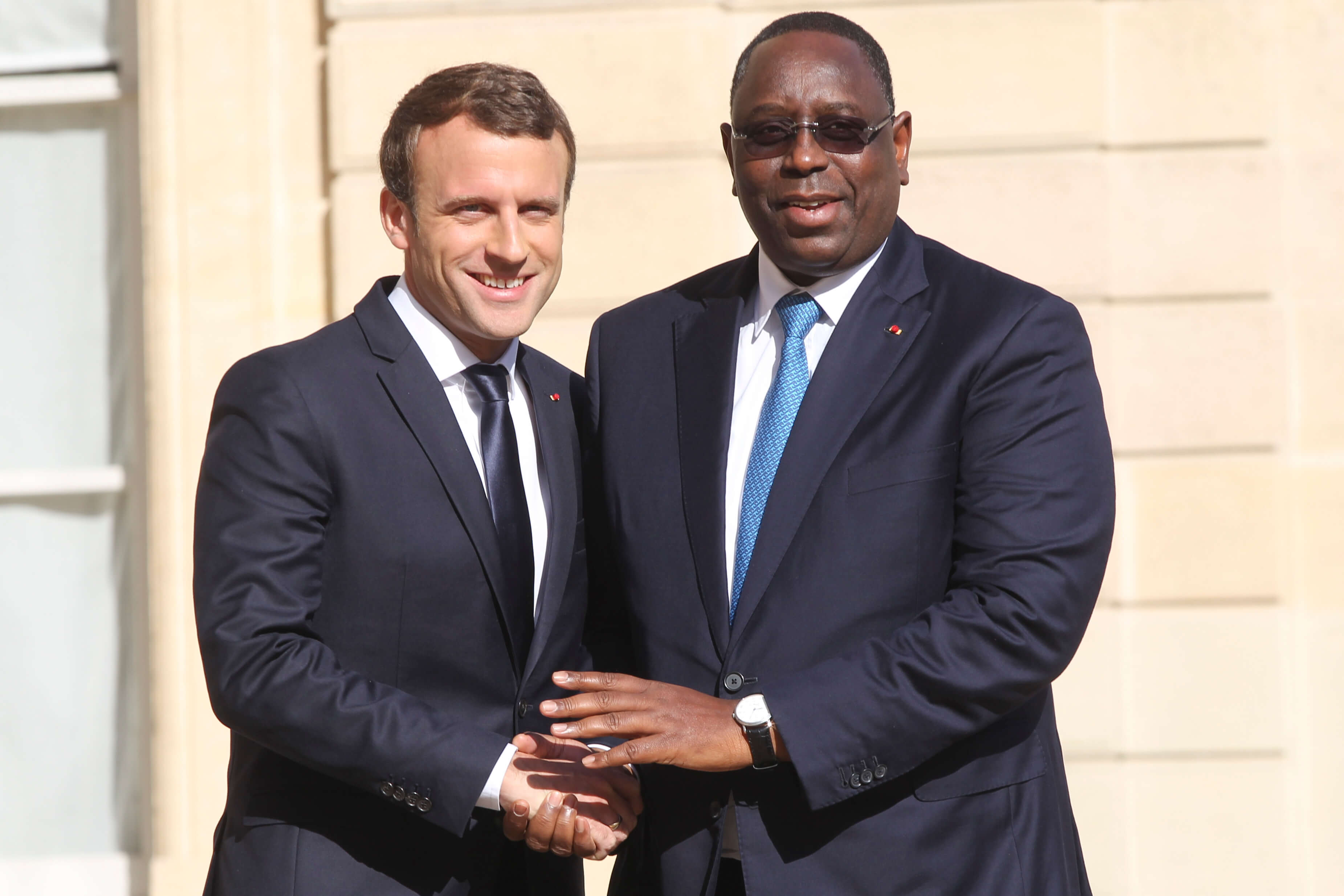

[image Emmanuel Macron and Macky Sall]

At the same time as these renewed calls for demonumentalisation were taking place, stories of artifact repatriation again began to circulate. In the UK, debates centred on institutions like the Pitt Rivers or British National Museums, but it is the French state of affairs that is most revealing with regard to the institutional procedures and the soap opera mea culpas that unfold during governmental public address. ‘I am from a generation of French people for whom the crimes of European colonization cannot be disputed and are part of our history,’ said French president Emmanuel Macron in 2017. So far Macron’s admission – or rather, his banal statement of the obvious – has resulted in movement on only one front, the repatriation of looted artefacts. A year later, in 2018, the French state commissioned a report on the ‘Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Toward a New Relational Ethics’ that made the case for repatriation, written by Senegalese academic and writer Felwine Sarr and French art historian Bénédicte Savoy. In its wake various articles have appeared in newspapers like the Guardian or arts and culture magazine’s like Frieze, talking up the proposed radical gesture of restitution that now seems on the cards between France and its former colony Senegal. Dakar, Senegal’s capital, has a new $30 million institution, the ‘Museum of Black Civilisations’, that is now also ready to house them (paid for by the Chinese, built by Chinese contractors and constructed by imported Chinese labourers). I’ve been to Dakar, visited its new museum and spoken to its director, and can write two things with confidence. First, the last thing on the average Senegalese person’s mind is the return of old sculptures; and second, the Museum of Black Civilisations is the most shoddily built institution I have ever seen. With all of the signage in either Chinese or French, the space looks more like a cheap hotel than a museum.

That the Museum of Black Civilisations is an underwhelming institution (to say the least) is no great tragedy for Dakar or Senegal. As with large scale institutions and national museums around the world, the importance placed on their existence is largely at the behest of state actors. After all, what function do large scale national museums actually perform? The notion that they are indispensable repositories of a nation’s history, the essential national memory bank that both reinforces and secures a nation’s sense of self, is both specious and a state serving rationale. Broadly speaking, national and state sponsored official public museums, fulfil a state led function of strengthening established historical narratives reinforcing a hierarchical view of society and a self-aggrandising view of national conduct as natural and right. Historically, most were built during the 18th and 19th centuries, periods in which the idea of nation, of a homogeneous collection of peoples linked by mythically enduring shared characteristics and reverences for societal tradition, were spreading. Museums were and are core rhetorical components that reinforce what historian Benedict Anderson called ‘the imagined communities’ that lay at the core of nationalist projections. They were and are meant to stand as the facts behind the fantasies and crucially, at the centre of this system is the fetishisation of objects and the impulse to preserve. Both are given universal status as behaviours that cut across cultural divides and ultimately make us human. They are not.

In Dakar the true colonial legacy of France is there in the economic encumbrance of the West African Franc (CFA). A currency imposed on Senegal during the decolonisation process by Charles de Gaulle, the CFA pegged Senegal’s currency to the fortunes of the French Franc first, then the Euro. Through a complex system of international currency protocols [see the video featuring economist Ndongo Samba Sylla above for details] the CFA essentially guarantees that Senegal’s economy will always be in a state of fiscal inertia, stymieing independence and self-determination, and arresting debt recovery and growth. The real economic beneficiary in this arrangement is France. Naturally, between Emmanuel Macron and the Senegalese president Macky Sall, it is most expedient to keep colonial conversations to the issues of artefact repatriation. Even as on the ground, protests and calls for the abolition of the CFA are regular, vocal and feature as a core demand of citizens and progressive parties concerned about the nation’s future. In contrast, nobody is marching in the streets for the return of artefacts, nobody is lobbying the government or stuck in prison for their object-oriented activism, and no opposition parties have repatriation as a key policy. The truth is, artefacts and exhibited objects are not important factors in the well-being and survival of anyone in Senegal, the continent of Africa and the rest of the world. In short, their presence or absence is not an explicit factor in a given individual’s odds of survival.

What can be said of the unimportance of artefacts and objects, can also be said of commemorative or celebratory monuments and statues. They too play their part in reinforcing aspects of a given narrative, they too stand as the concrete evidence intended to ground myth or sentiment in physical presence. But, in the lived, daily realities of average citizens, monuments and statues are almost completely ignored. They are things we walk past, things we know nothing about, things that pigeons and midnight drunks use as a public toilet. However, in the cosmetic regime, they are pawns in the game of public accountability, and are the first pieces to be moved into play whenever ‘colonial’ debate or agitation surfaces. Sure, the state will resist calls to pull down or erect a given monument or statue, and sure the right-wing press will decry the rampant political correctness of society, but it is all part of the dramaturgy of distraction. In other words, when they talk about pulling down or putting up a monument, look at the policy they are trying to hide, look at the system they are trying to protect.

Morgan Quaintance is a London-based artist and writer. His moving image work has been shown and exhibited widely with presentations in 2020 including: Curtas Vila Do Conje, Portugal at which he recieved the Best Experimental Film award, and CPH:DOX at which he received the New Vision Award, both for the film South (2020); Oberhausen Film Festival, Germany; European Media Art Festival, Germany; Alchemy Film and Arts Festival, Scotland; Images Festival, Toronto; International Film Festival Rotterdam; Punto de Vista Festival in Pamplona, Spain; and Third Horizon Film Festival, Miami. Over the past ten years, his critically incisive writings on contemporary art, aesthetics and their socio-political contexts, have featured in publications including Art Monthly, the Wire, and the Guardian, and helped shape the landscape of discourse and debate in the UK.

It is hard to think of a dance or a ritual as a monument, perhaps because movement has an intrinsically ephemeral quality compared to the stability or objecthood of a traditional solid memorial monument. This is the primary reason to consider a performance piece for this occasion. Another is the notion of memory and how movement can be catalogued and remembered, preserved in our collective unconscious, as in choreographer Boris Charmatz’s project for the Tate Modern.

The Rite of Spring is a dance piece par excellence, a must for directors or choreographers and perhaps even dancers. Indeed, it is synonymous with the birth of modern dance and considered a classic that is hard to avoid and tempting to redefine or rediscover. It was originally choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky and scored by Igor Stravinsky, and first danced by Sergei Diaghalev’s Ballets Russes in Paris in 1913.

[img]

There have been many adaptations and variations, from Mary Wigman to Martha Graham and Pina Bausch, who first introduced earth as a material, or Yvonne Rainer. The piece was to be performed by a cast made up entirely of dancers of color for the first time, but the production was cancelled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

What I am most interested in tapping into are the notions of appropriation, earth, dance, rituals, and retribution and sacrifice. There is at the heart of this piece a connection with the earth, origins, and roots, which could be interesting to investigate precisely in an era when this notion is so highly contested.

I would like to bring these different signifiers or references to the Franska tomten site and think of them as metaphors for what this piece of land represents, what it acts as, or what it is meant to replace. I ask myself the following questions:

Could we think of dance as a reparatory ritual that could illuminate the parceling or trading of land by its legal owners—and point out the injustice in such trade?

Could earth elements, a dance, or a group of people gathered once a year create a kind of homage or monument to the memory of the trade that once was?

I would like to propose that each year on the same spot a group of people dance a small section of the Rite of Spring with earth, as it was danced by the Pina Baush company. It is a way to remember where this piece of land comes from and to reenact how it was separated from its people, how it came to symbolically represent the piece of land for which it was traded, which is far away from the reality of the city it is now in. I keep thinking of The Wretched Earth, the 1961 book by psychiatrist Frantz Fanon that has inspired a lot contemporary postcolonial discussions.

I am no theorist, but maybe I see in this title a way to bring some elements together to create not binarism but instead perhaps a bridge.

In a nutshell, I see this a bit like an opportunity I once had to go to the Dominican Republic. Davidoff Cigars used to have an artist residency there, and I brought my class from the Berlin University of the Arts to do an exchange with a local art school whereby both learned about performance art and exchanged ideas, including meeting with the late Alanna Lockward, who invited Charo Oquet and Maxence Denis of Haiti for a heated conversation with the students. We produced a performance, which was performed both in the Dominican Republic and in Berlin.

I was born in French Guadeloupe, and maybe there is a reason why this project, which addresses a nearby island, does not leave me totally unmoved.

I will try to summarize here in a few words how I see this project unfolding and its possible ramifications, as well as the aspects of it that may be still under development or even questionable.

I would propose as a project that once a year in the spring a group of children from a local school (each year a different school) could learn a small section from the Rites of Spring, Pina Bausch version. They could perform a ten-minute portion of the piece on waterfront near the Delaware monument by Carl Milles, facing out to sea.

The turning point of this yearly performance, which could act as a kind of monument, would be a requirement to obtain a certain amount of soil from St. Barts, which would be stored and used each year as a ritual for the performance, just as the stage hands bring the earth that the performers use in the Pina Baush version of The Rites of Spring.

The earth could be stored in a specific container on the plaza with a plaque telling when and how and why it is activated each year. This makes it a site of active

re-membrance in the original sense of putting the members, parts of the body, back together (in this case the movements). It would acknowledge the past of the site, but also address the perennial nature of the dance, as it is embodied by younger people who learn about it while positioning themselves in space, but also learn about the history of this place and their position in it, hopefully giving them also the same sense of emancipation I had when I first learned Yvonne Rainer’s piece Trio A.

As I wrote above, I welcome questions and debate about the elements of this proposal, such as which schools, which age students, and which sections of the dance piece? Should it be performed with music or without? How should the soil be transported and stored? What does the plaque say, and what is it made of? I believe these questions could remain open at this stage.

Image credit

Dancers at the premiere of Sacre du Printemps, choreography Vaslav Nijinsky, 1913. © picture-alliance, akg-images

The Rite of Spring by Pina Bausch restaged in Senegal by Salomon Bausch and Germaine Acogny

Jimmy Robert (born 1975, Guadeloupe) lives and works in Berlin. Robert works with diverse media including photography, collages, objects, art books, short films and performance art. In his explorations of the relationship between images and objects, Robert draws attention to the dynamics of different surfaces. Questions of identity and its representation are his main interest, and he uses a variety of references to literature, art and music to emphasise the fragility of the materials he uses. In some performances Robert’s body becomes a projection surface, where tension between the portrayal and the content reveals the relationship between appropriation and alienation. In previous works, Robert has explored the politics of spectatorship by reworking seminal avant-garde performances in ways that complicate their racial and gendered readings. Jimmy Robert is currently professor of Sculpture and Performance at UdK, Berlin.

The artist participated in the recent Chicago architecture biennial and is currently working on a touring mid-career survey at Nottingham Contemporary and CRAC de Sète then Museion Bolzano, to open in 2021. In recent years, Robert has exhibited at 8th Berlin Biennale of Contemporary Art, Berlin; Tate Britain, London; WIELS, Brussels; CCA Kitakiushu Project Gallery, Japan; Cubitt Gallery, London; Neuer Aachen Kunstverein, Germany; CAC Bretigny, France, KW, Berlin, and performed at MoMA and Performa 17, New York. Jimmy Robert was the 2009 laureate of the Follow Fluxus–After Fluxus grant. Solo shows include presentations at Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris and Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Chicago (2012), The Power Plant, Toronto (2013).

Att vara svart konstnär är att vara kringskuren från alla håll. Det finns så mycket förväntningar på vilken konst man bör göra och vilka ämnen man bör behandla. Det mest radikala jag kan göra för att bryta mot denna mentala kolonisering är att bortse från de förväntningarna. Att göra abstrakt konst kan vara lika politiskt som att göra konst med representation. Det övertygar dig om att det du tror dig veta inte är allt. Det finns mer bortom.

Mina skulpturer är illustrationer av den här känslan.

När jag fick förfrågan att ge min respons till Franska tomten ville jag göra något personligt för platsen. Något inifrån. Spår från mina performance. Två skulpturer som blir till en. Utan varandra har de ingen funktion. De vill heller inte ha någon funktion. Det de vill är att få vara. Bekymmerslösa. Något jag aldrig själv har fått uppleva.

Går det att göra en förlängning av mig själv till en plats med så fasanfullt förflutet. Kan ett människoöde någonsin säga något om en annan människas öde och vems historier får berättas och av vem och hur. Kan två platser tala med varandra. Jag tecknar en koreografisk karta som sträcker sig ut och bildar ett annat universum där det abstrakta kommunicerar tydligare än de symboler och skrifter vi är inpräntade med.

Det finns rotsystem som växer mellan platserna. Hela vägen från Saint-Barthélemy till Franska tomten och tillbaka igen som en cirkelrörelse. De två verken försöker kommunicera med varandra som en utstrålning, varning, trygghet och beskyddare av varandra. En besvärjelse att vi aldrig får sudda ut historien och gömma spåren av koloniseringen. Aldrig någonsin förenkla. Det går inte att förklara kolonisering med enbart fakta. Vi måste motarbeta den med konsten.

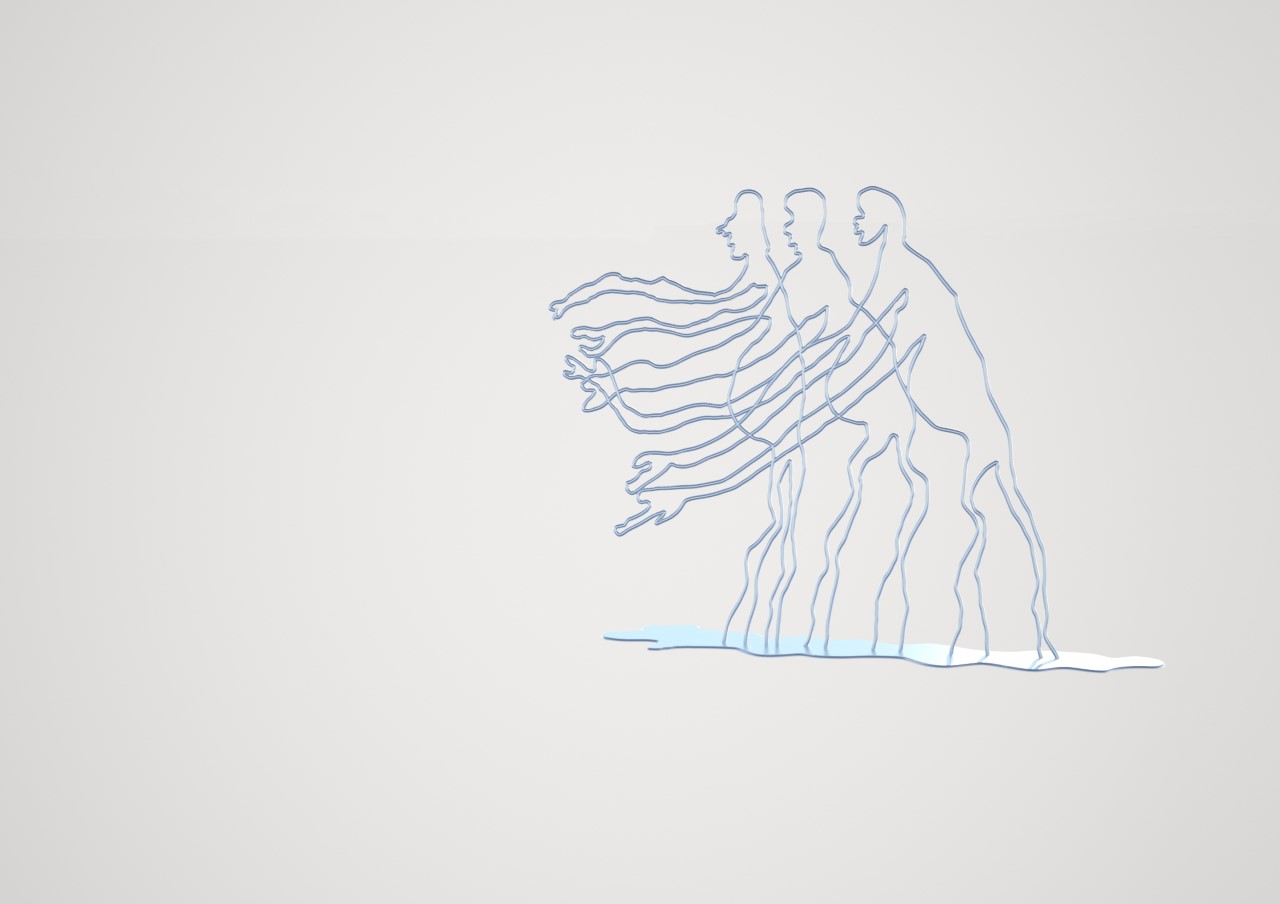

Från Saint-Barthélemy reser sig tre abstrakta gestalter ur mitt inre – växer ut från marken och legeras tillsammans. Fanns de där hela tiden?

Jag håller fast vid min rätt att få vara komplex. Det är den starkaste manifestation jag kan göra av min egen frihet. Jag har gjort två förslag i form av tredimensionella gestaltningar av den konst jag gör. Ett förslag för Franska tomten och ett för Saint-Barthélemy.

Förslag till Franska tomten

Renderingar av skulpturer i rostfritt stål i mänsklig skala. Dimensionen på konturerna är 36mm.

Renderingar av: Nils-Erik FranssonFörslag till Saint-Barthélemy

Renderingar av skulpturer i rostfritt stål i mänsklig skala. Dimensionen på konturerna är 36mm. Höjd 1750mm.

Renderingar av: Nils-Erik Fransson

Being a black artist implies being constrained from every possible angle. The expectations of the art world concerning what art black artists are supposed to make are both limiting and suffocating. The most radical thing I can do to end such a colonization of my mind is to sidestep those expectations. For example, I believe that making abstract art can be equally political as making representational art in the sense that it convinces you that what you think is not all there is to know, and that there is a beyond to what you can see.

My sculptures are illustrations of this feeling.

When I was asked to give an artistic response to Franska tomten in Gothenburg, Sweden, I wanted to make something site-specific and personal, something from within me. Remnants from my performances, two sculptures that become one. Without the other neither of them has any function, and nor do they want any function. What they are concerned with is being, and being at ease, something that I have never experienced myself.

Can I really make an extension of myself as a way to connect to a place with such a horrific and unforgivable history? Can the fate of a person ever say something about the fate of another one? Whose stories are allowed being told, and who are to tell them, and how? Can locations situated far apart actually communicate with each other?

I draw a choreographic map, which expands and offers another universe where abstractions communicate more clearly than the descriptive symbols and writings that have been imprinted on us.

A root system grows between these places—all the way from Saint Barthélemy to Franska tomten and back again in a circular movement. The sculptures strive to communicate with each other as a kind of an emission, a warning, and a safe haven – each protecting the other; An enchantment reminding us that we must never obliterate the historical traces of colonialism and its remnants in the now, and never ever simplify for its own sake. Colonization cannot be explained away through facts alone, we also need to decompose it with art.

Three abstract figures from Saint Barthélemy emerge from within me. They spring forth from the ground and get alloyed together. Have they always been there?

I claim my right to be complex, for that is the strongest manifestation of my own freedom that I can make. I have made two proposals in the form of three-dimensional expressions of the kind of art that I make: One proposal for Franska tomten and one for Saint Barthélemy.

Image credits

Proposal for Franska Tomten

Renderings of sculptures in stainless steel at human scale. The dimension of the contours is 36 mm.

Renderings: Nils-Erik FranssonProposal for Saint Barthélemy

Renderings of sculptures in stainless steel at human scale. The dimension of the contours is 36 mm. Height: 1750 mm

Renderings: Nils-Erik Fransson

Fatima Moallim works with manipulations of space and time in a merging of inner and outer worlds, fantasies and memories. Her project Flyktinglandet draws from different aspects of her parents’ flight from Mogadishu, Somalia to Sweden. The alienating experience of relating to conflicting realities is manifested using her self-invented performance method, where she makes temporary large-scale drawings in relation to the existing architecture and the feelings and moods present in the room. Her recent series of sculptural objects called Documentation are based on knowledge gained from her ongoing self-studies. The installations are physical representations of an abstract parallel reality, authentic artefacts beyond the realities of life.

Fatima Moallim is a self-taught artist born 1992 in Moscow. She has exhibited site-specific works at Moderna Museet Stockholm, Göteborgs konsthall, Marabouparken, Zinkensdamm metro station in Stockholm and on the glass facade of Bonniers konsthall.

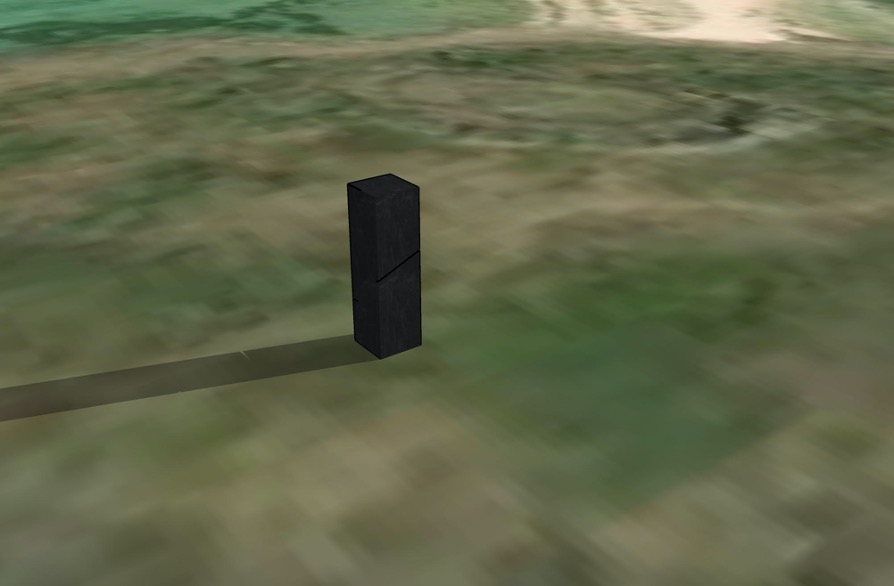

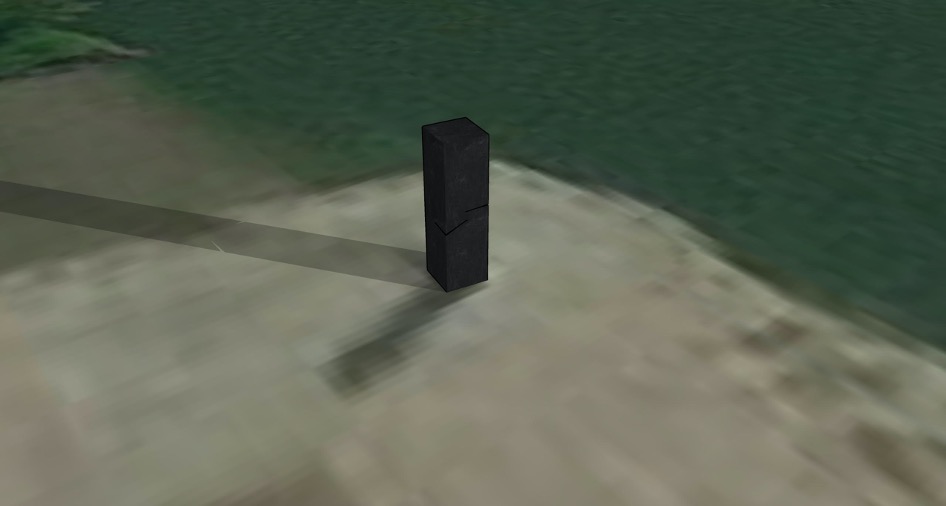

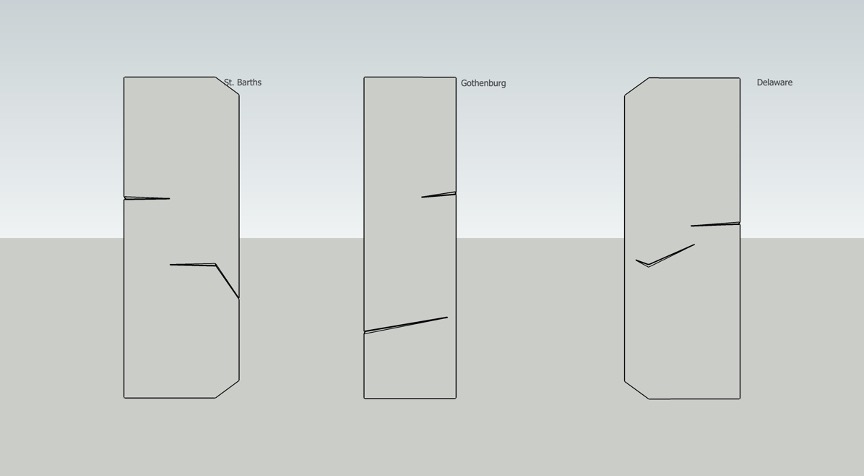

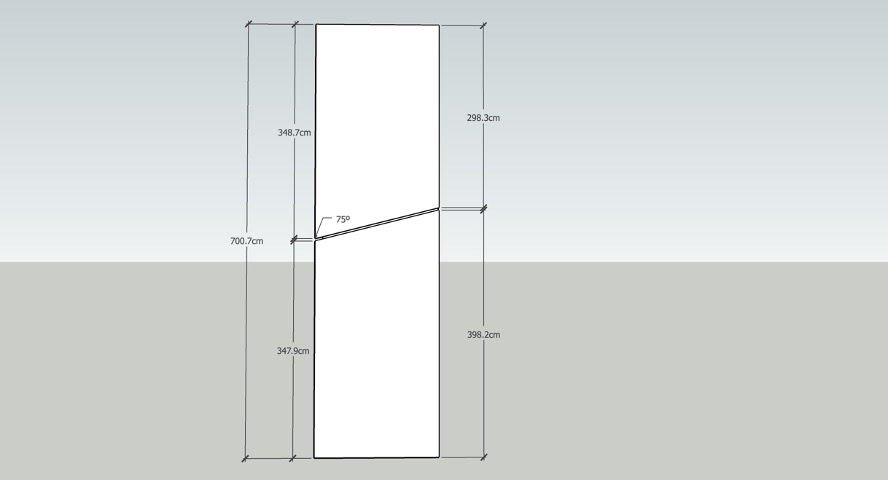

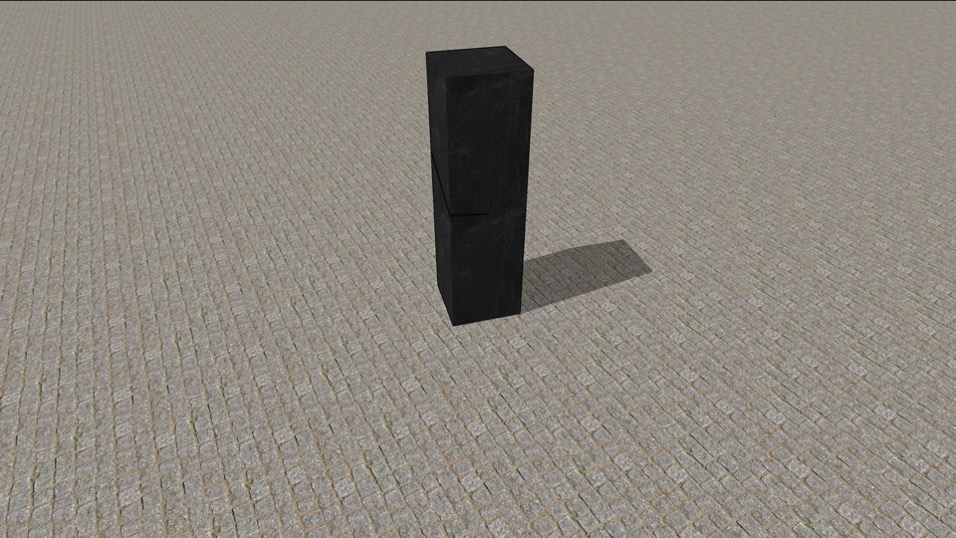

New Monument for Franska tomten is a distributed monument that commemorates Sweden’s entrée into the transatlantic colonial world. The monument replaces and expands the Delawaremonumentet at Stenpiren in Gothenburg, Sweden – a copy of a 1938 monument designed by sculptor Carl Milles that stands in Fort Cristina Park in Wilmington, Delaware, the site of the first Swedish colony in America. The new monument replaces both of these – Milles’ copy and original – and adds a third iteration, on the island of St. Barts, Sweden’s sole, short-lived colonial holding (1784-1878). New Monument for Franska tomten links these three locations, marking them as operative in Sweden’s political and economic history on the global stage.

New Monument for Franska tomten replaces Milles’ black granite and bronze sculptures with iron plinths of their same basic dimensions (h: 7 m; w: 200×200 cm). Each plinth has a gash cut into it that marks the line between direct sunlight and shadow at sunset on three specific dates.

The gashes mark the sunset on:

Nov 1, 1637 (departure of first settler expedition from Gothenburg to America)

July 1, 1784 (transfer of Saint Barthelemy to Sweden by France in exchange for Franska Tomten

October 31, 1786 (establishment of Swedish West India Trading Company on Saint Barthelemy)

In each location, the monument functions as an abstracted sundial, the sun’s position on it moving with the 24 hour cycle. Each day the sun passes over the timestamp gashes, aligning approximately with the marking. The marking, of course, never changes, forever noting the date and time of the three historic moments. Importantly, though they mark specific dates/times, the monument’s relation to this time is rendered cyclical – the cycle of the sun slips with the march of history.

New Monument for Franska tomten questions the effectiveness of the commemoration of events through representative monuments. It is a materialist, para-symbolic monument to Sweden’s political and economic history, particularly its imbrication in colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. New Monument for Franska Tomten is materialist first and foremost through its actual materiality–made wholly of iron, which has been one of Sweden’s main exports for centuries and was also used as a form of currency in the Atlantic Slave Trade (“voyage iron”)–as well as through the nature of the events it marks and how it marks them.

“The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the “emergency situation” in which we live is the rule. We must arrive at a concept of history which corresponds to this” – Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History”

New Monument for Franska tomten specifically commemorates crucial moments of economic and material exchange in Sweden’s interaction with the rest of the Western World. In this sense the monument makes an argument about history itself, the process of nation-making alongside the long arc of globalization, and slavery’s material and philosophical undergirding of this process.

“The blank face of Minimalism may come into focus as the face of capital, the face of authority . . .” – Anna Chave, “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power”

New Monument for Franska tomten is a monument to a brutal history, and its minimalist, materialist aesthetic renders this history appropriately. The question of whether, or how, to represent or mark the horrors that are the engine of our world is a necessary one, and cannot be solved by choosing to highlight the brighter moments in the past. A minimalist, materialist approach to the making of monuments both circumvents the problem of representation and adequately speaks to the reality of the past’s impact on our present.

Aria Dean (born 1993) is an American critic, artist, and curator. Dean is the assistant curator of net art and digital culture at Rhizome. Dean’s writings have appeared in various art publications including Artforum, Art in America, e-flux, The New Inquiry, X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly, Spike Quarterly, Kaleidoscope Magazine, Texte zur Kunst, and CURA Magazine.

Dean has exhibited internationally at, a.o., Metropolitan Art Centre (MAC), Belfast, Ireland (2019); Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond (2019); Het Hem, Amsterdam (2019); Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia (2019); Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo (2018); Schinkel Pavillon, Berlin (2018); and The Sunroom, Richmond, Virginia (2017), Arcadia Missa in London.

I’m very grateful for being invited to this seminar conversation, especially since this specific Gothenburg context speaks to something that is so important to accentuate in exceptionalist Nordic contexts: the materialization(s) of colonial memory. What has fascinated me, especially during the last decade, is how frequently, Swedish exceptionalism allows the “us” that counts (ie, the white majority) to forget about our country’s colonial legacy, and reclaim – again and again – a position of feigned innocence (Wekker 2016).

In their article “Listening with Gothenburg’s Iron well”, Nana Osei-Kofi and Lena Sawyer reflect critically on “coloniality hidden in plain sight” (Osei-Kofi, Sawyer 2020: 56). I find this formulation “hidden in plain sight” significative of the many ways in which Gothenburg’s, and in a larger perspective, Sweden’s colonial legacy gets relatively limited attention, at least in mainstream public discourse. How is that process made possible in the everyday, to hide coloniality and colonial memory in plain sight? What visual regimes, which delimited fields of vision are required in order to see but not notice coloniality?

I would like to reflect on the seemingly given, alleged political transparency of the past, and its pervasive (or continued) cultural inscription of racial hierarchies and colonial relations as non-problematic. Furthermore, I want to reflect on two aspects of “work” required in the everyday not to see what it signifies – to bury, to hide, ignore, or refuse to see the signs that must unavoidably be seen in public and domestic settings? Taking my point of departure in materiality and scale, I will focus on the smallest and largest of everyday objects that we encounter: monuments and household objects related to Delaware jubilees. Visual field (our). How can that which is so intensely visible in city landscapes sink into a state of oblivion?

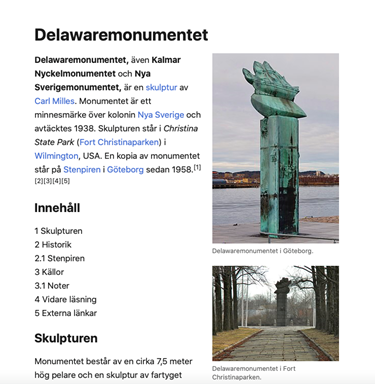

Even if Sweden’s national memory does not allow for a straightforward acknowledgement of its part in the imperial adventure, it effortlessly accommodates recurrent celebrations of various phases of it. One such example is the celebration of the Delaware Jubilee, commemorating the establishment of “New Sweden” in 1638 (1638-1655). According to historian Adam Hjortén, it was first commemorated in Minneapolis in 1888, without Sweden paying that much attention (Hjortén 2013). In 1938, the celebration of Delaware coincided with king Gustav V’s 80th birthday, and the passing of a new law that gave citizens the right to a two-week vacation (Habel 2002; Hjortén 2013). Twenty years later, in 1958, the celebration involved raising a monument, created by the artist Carl Milles; it was placed in the Fort Christina Park, Delaware. According to Hjortén, over 200 000 Swedes had donated money to raise the monument, and a replica was also placed at the Stone Pier in Gothenburg the same year.

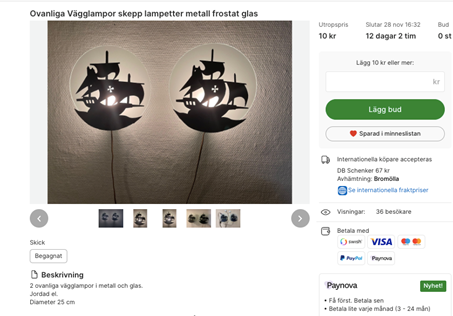

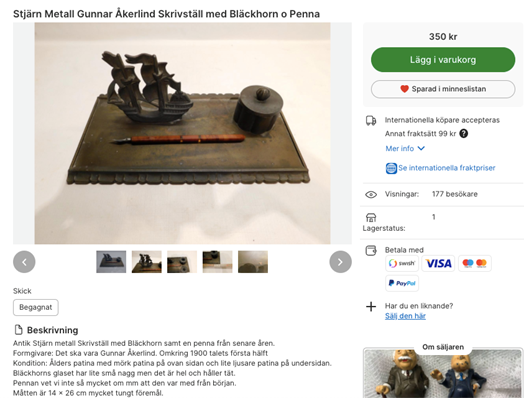

Something that I find interesting in these celebratory contexts, are the many household objects that surrounded the recurrent commemorative Delaware events. In my earlier research, I have discussed several examples of how cultural and popular scientific discorses and values are negotiated through the concrete handling of objects (Habel 2005, 2011, 2012, 2013). Following the lead of Anne McKlintock, I’ve exemplified ways in which images and object of race and empire enter domestic spheres. Household items such as writing sets, stamps, candle-sticks, book ends adorned with iconic colonial ships were some of the objects circulated and gave Swedes the opportunity of taking the jubilee and the pride over “New Sweden” in-hand.

Considering Sweden’s relatively small scale of colonial conquest in the New World, material practices and commemorating objects appear to have played important roles for the identity of Sweden, which had increasingly lost its former position as a regional colonizer, and regionally dominant kingdom. In my presentation, I will talk more about how material practices and rituals of commemoration have contributed to inscribing Sweden’s significance as colonizer.

Ylva Habel is a film and media studies scholar, based in Stockholm Sweden. Her research draws on black studies and postcolonial, critical race and whiteness studies, specifically revolving around the affective economy of Swedish, “post-racial,” exceptionalist discourses connected to welfare values. Her interdisciplinary approach often combines these perspectives with the optics of media history, visual and material culture. She is currently a free researcher, affiliated to CEMFOR, Uppsala University.

In 1832, only two years after the start of the colonisation of Algeria by the French, the French government superposed a new landscape that would replace the old. Ordering the creation of a botanical garden in Algiers called Jardin d’Essai du Hamma, or Test Garden of Hamma.

Test gardens were used in colonies for economical purposes, to produce fresh vegetables and fruits for the metropol. The first plants the French tried to grow in Hamma were cotton, tea, sugar-cane and vanilla.

In a few years, the gardens grew from 5 hectares to 18. In 1867, the Hamma exceeded 57

hectares and amounted to a total of 8214 species. In which half originated from a tropical climate.

Around the entire Algiers the military attains the responsibility of planting trees beside the roads, in turn creating squares. Molding and transforming the city into that of its European double.

In 1914, the Hamma turned into a leisure park, opening its gates to the public. For the 100th year anniversary in 1930, marking the French colonial rule of Algeria, the park was fixed and made complete by water ponds. The Museum of Fine Arts perched upon the hill located within the center of the park allows for a classical perspective stretching out to the sea, a monumental and prestigious building completing the civilisatrice mission.

I am walking into this park. This is a place I am familiar with, this is my garden.

Viewed from the Museum of Fine-Arts, the perspective is impeccable. And then the sea.

On each side of the perspective, lies what I call “the jungles”, or overgrown plots of lands that are part of the Hamma gardens. In their tests and experiments, the French had the dream of finding in Hamma the ultimate land of fertility, a land that could acclimatise all plants gathered through their discoveries of the new worlds.

My overgrown plots of lands are the result of this illusion. A colonised body composed of

overlapping stories and histories. Some well known and some untold, and all the gaps in

between. I have inside this cacophonic body, the totality of the world.

As opposed to this image of abundance, Franska tomten is a grey space, and very little is made visible to remind us from its past. In the context of a speculative monument or memorial, I would like to think of Franska tomten as a Test Garden, and be inspired by the Test Garden of Hamma to re-contextualise this space.

Can we superpose these landscapes, being themselves composite and the result of multiple superpositions?

Can we investigate the Test Garden of Hamma in Algiers and find the Caribbean?

The methodology of A Memorial to the French Plots of Land (working title) is inspired by Le Traité du Tout-Monde by Edouard Glissant, and is borrowing concepts such as creolisation, rhizome and relation as tools for reasoning, composing and accomplishing the piece.

By investigating the Test Garden of Hamma, the aim is to unfold the many stories and histories of our “cacophonic bodies”, drawing in their metaphoric and physical potentialities, and reviving the existing links despite their distant geographies.

I envision a team of botanists, researchers and people with testimonies and experiences to be the agents of this re-contextualisation, and reciprocally use Franska tomten as the recipient of this research for a period of 3 years until the official (delayed) 100th years anniversary of the inauguration of the city of Gothenburg in 2023.

This 3 years period will allow for exercising Le Traité du Tout-Monde, resulting in discussions, field-works and workshops, attempting the impossible acclimatisation of the Hamma gardens in Gothenburg, but first and foremost the dissection of its composition, metaphors and meanings.

At this point of the process, this proposal remains of speculative endeavour and a more concrete plan of action will be envisioned at a later stage.

Hanan Benammar (born 1989) is an Algerian/French artist based in Oslo who works conceptually on geopolitical, environmental and social issues. As part of her artistic practice Benammar organises and curates art projects. Benammar is a graduate of the Art Academy of Oslo (MA) and of Dutch Art Institute i Nederland (MA). Benammar has exhibited and performed at a.o. Black Box Teater (Oslo), Le Cube (Rabat), Kunstnerforbundet (Oslo), Lofoten Sound Art Symposium (Svolvær) and Radikal Unsichtbar (Hamburg).